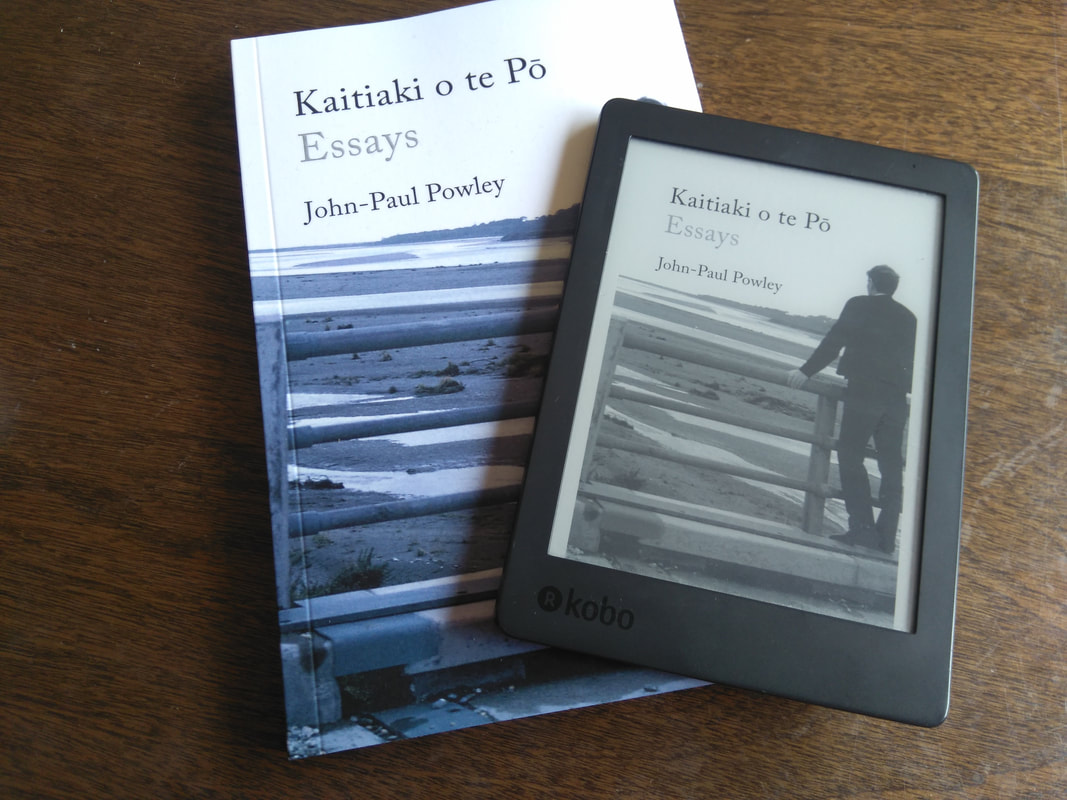

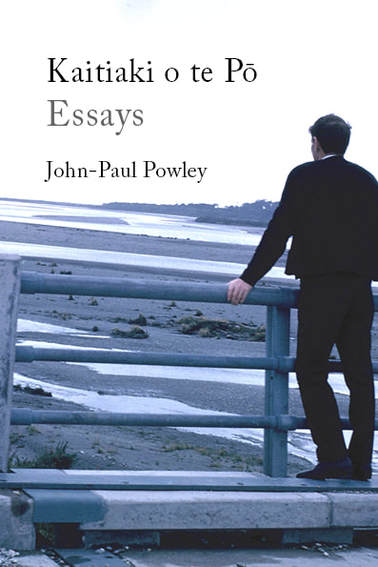

With the help of MeBooks, Kaitiaki o te Pō: Essays by John-Paul Powley is now available as an ebook. It's available as both an epub and mobi, so you can read it on your Kindle or Kobo or any other ereader, or on your phone or tablet. Or even your computer, though that sounds a bit awkward.

You can buy and download it:

from the MeBooks website

from Kobo

from Amazon.