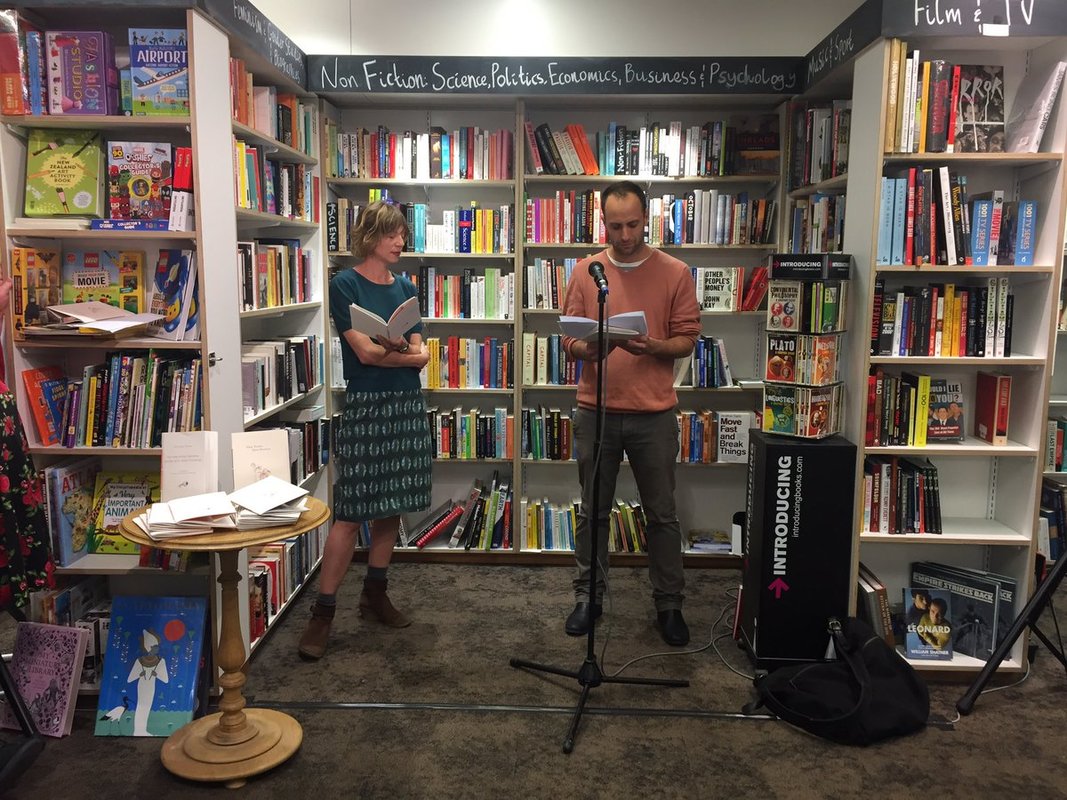

You can catch Anna and Luc reading more French poetry in French and English at LitCrawl in Poetry In and Out of Translation, 6 pm, Hashigo Zake, Saturday 11 November.

Below is Helen Rickerby’s launch speech.

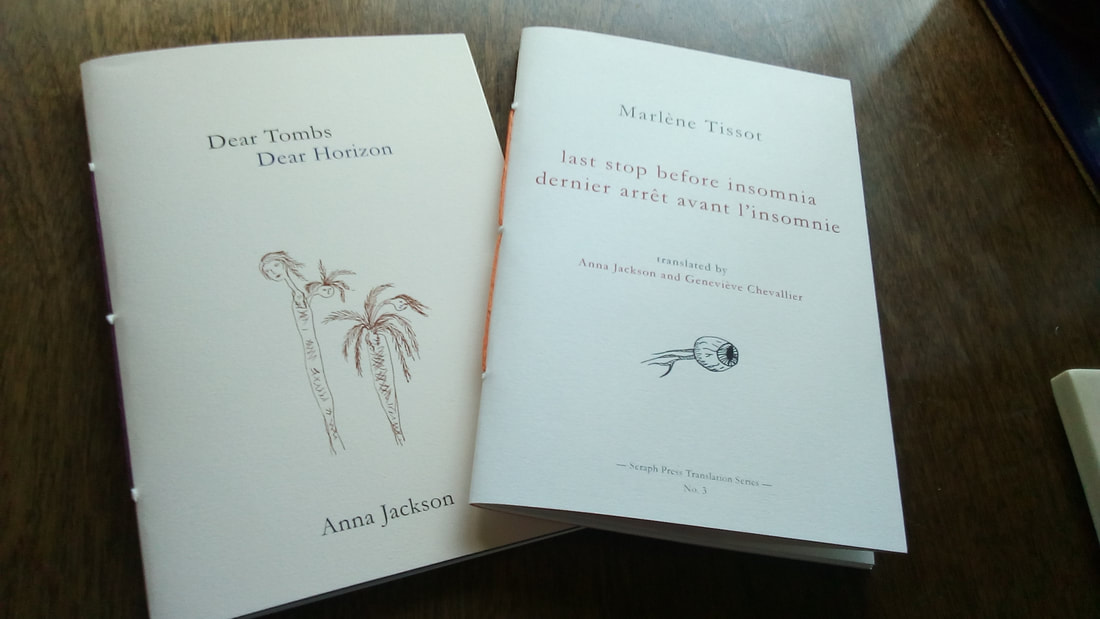

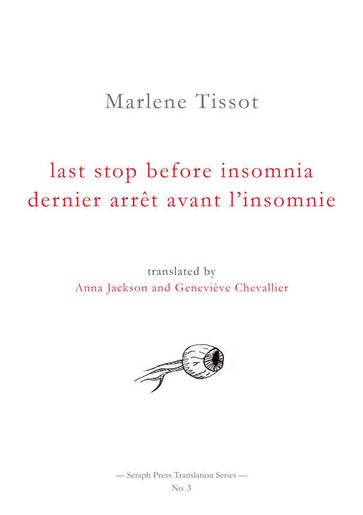

Kia ora, bonsoir, good evening and welcome to the launch of these two chapbooks with a French connection – Dear Tombs, Dear Horizon, by Anna Jackson, and Last Stop Before Insomnia by Marlène’s Tissot, translated by Anna Jackson and Geneviève Chevallier.

I’m Helen Rickerby and as Seraph Press I’m the publisher of these two books.

As well as the French connection, the other connection between them of course is Anna Jackson. You will all know her as an amazing poet, and scholar and teacher. I’m also lucky enough to have her as a very dear friend, and so it’s especially delightful to be launching these two books with her.

Both of these books came about because Anna was the Katherine Mansfield Menton Fellow last year. Not content to just work on her main poetry project, she also worked on various side projects and caught the translation bug after meeting academic and translator Geneviève Chevallier.

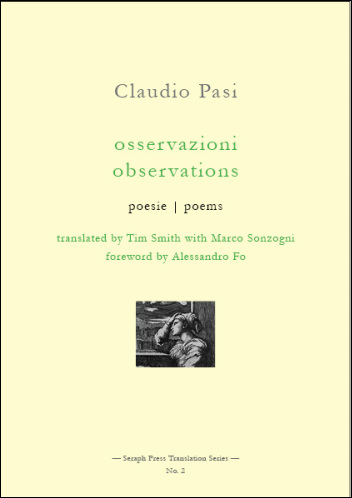

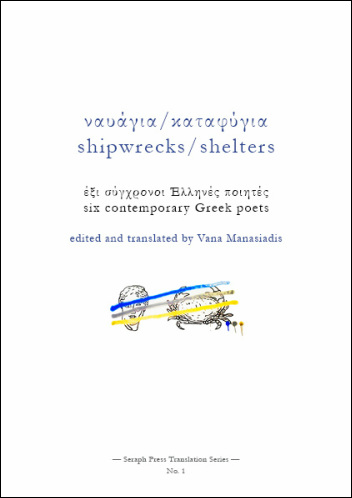

Last Stop Before Insomnia, a delightful introduction to the poetry of French poet Marlène Tissot, resulted from that connection, and is now number three in the Seraph Press Translation Series, which I started about a year ago with my series co-editor Vana Manasiadis. In November last year we launched the first two books in that series – Shipwrecks/Shelters, a small anthology of six contemporary Greek poets, translated by Vana, and Observations, a selection of poems by Italian poet Claudio Pasi, translated by Tim Smith and Marco Sonzogni.

The series was Vana’s idea originally – she had just returned from living in Greece for almost a decade, and was feeling the lack of translated literature here in New Zealand. She got me excited about being able to share different poetic voices and celebrate different poetic languages. Our aim for the series is to bring to a New Zealand audience contemporary poetic voices from languages other than English, and to make connections with literatures and writers from other parts of the world. We want them to be bilingual tasters of something fresh and new. Our next collection, which we are very excited about, is a wee volume of seven Maori women poets, whose poems, which were originally written in English, are being translated into te reo Māori. It’s being edited by Maraea Rakuraku and Vana.

Anna is going to talk a bit more about Last Stop Before Insomnia a bit later, and she and French translator Luc Arnault will do a bilingual reading, which is something I’m very much looking forward to. But first I’m going to talk about the other chapbook we’re launching tonight – Dear Tombs, Dear Horizon.

This was written while Anna was in Menton, being the Katherine Mansfield Fellow, and began as a sort of poetic travel diary in which she recorded things she did, things she saw, etc. The initial (and longer version) that she sent me just before she came back, very clearly showed how it began more as a diary, and it still contains many of those interesting and delightful in itself observations. I’m very fond of anecdotes such as which of the previous Menton fellows was the favourite of the expats, and observations like how the bats flying past the balcony look like cut-out bats. But the poem quickly became more than simply a recording thing, but a thinking thing – a poem in which you see the thinking and mulling and connecting.

I’m really interested in what poetry can do – what can be done in poetry, and many of you will know that in a bit over a month Anna and I, with our friend Angelina, are running a conference about poetry and the essay. And, because it’s my new obsession, I’m thinking about this long poem very much as an essay – not in that it has an argument or a thesis – it doesn’t present the answers – but in that it is enquiring and considering, It is thoughtful and mulling. Some of my favourite sections are ones which take something she is reading, an idea of someone else’s and she turns it over and connects it with other things. Her reading is varied, and includes Robert Dessaix on Turgenev, Martin Heidegger, Catullus, articles about octopuses and her predecessor Katherine Mansfield.

I’ve been thinking about how a recurring theme of the poem is the idea of looking back, finding new places to look back from, new things to look back at. Sometimes literally, as Anna writes:

I walk up and down

impasses and traverses, looking for new

angles to look back from. I go up

lifts and behind bins, urban hiking

Or the time she and her friend Rose go behind the apartment building to see what it looks like from behind:

It’s like not being able to see

the back of your head, she worries,

and I think of the Catullus poem about

the poet who reads his poetry oblivious

to how awful it is. What flaw am I

carrying around like a backpack

I cannot see,

But the looking back is often more figurative – such as the tense used by the Roman letter writer – a complicated looking forward to look back into the past of the present:

(“I was writing this in the garden…”) – thinking ahead

to what will be the present moment in which

the recipient reads the letter, already

imagining their present moment of writing as having

taken place in the past,

Similarly the poem ends with a looking forward to look back – when Anna herself – as the poet at least – I think we can assume that the narrative voice of the poem is fairly close to actually being Anna, though it always dangerous to assume, I think we can fairly closely map the narrative voice of the poem to the actual Anna – writes a about wondering about writing the poem we have just read:

I think of

starting the poem “Dear Tombs,” and

wonder whether perhaps I should

try writing the poem

in terza rima. Really I just want

to pile into it everything I have got.

All this looking back isn’t just idle, but a way to get a better perspective – as she says:

literature does give us

another place to look back from

Having said that this long poem doesn’t really have a thesis, I think I want to revise that statement, because I think this is an understated but really powerful argument for the value of literature to our real world.