I am obsessed with mysteries and ghosts. Each of these figures felt ghostly to me in some way, in the sense that they were complex and unknown and existing only in traces. It was only after I’d begun writing poems about the other four that I decided to include the school ghost – but they all are in a way.

In the case of all of them I think I can pinpoint a tingling moment that made me want to write about them, much like when I peered into the doorway of the ghost tower. With Phyllis Porter, it was when I saw the newspaper clipping in the Opera House (that really happened) and with Katherine Mansfield, a less obscure ghost but a kind of looming figure nonetheless, I think it was when I saw a cross with her brother’s name on it in the grounds of Parliament. These things really happened. So I had to investigate.

Did you deliberately choose to write about New Zealand women? If so, why?

I think so. When I started my MA at the International Institute of Modern Letters I had read hardly any contemporary NZ poetry and I felt like I didn’t know much about New Zealand history at all, having partly grown up overseas. So I read as much as I could, and found myself searching very close to home for subjects to write about.

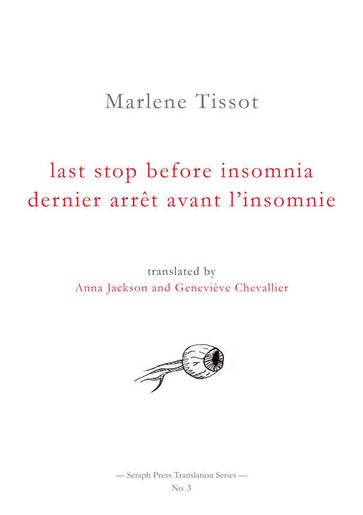

I’m interested what connects us to people from the past. People pay lots of money for objects once owned by dead famous people because it makes them feel closer to them. People go on pilgrimages and touch trees and doorknobs that legendary figures once touched. As a child I lived down the road from Katherine Mansfield’s birthplace. I wondered what it meant that Mansfield and I grew up beneath the same hills and swam in the same bays and walked on the same bits of footpath – or does it mean nothing at all? I think lots of people have wondered the same thing before about lots of legendary figures from the past. But what about all those people who aren’t legendary, who also inhabited the same space that I do now? I became obsessed with this connection between memory and physical objects and physical spaces. While writing, I was keenly aware that the distinctive New Zealand landscape (and the sea, the harbour, the same moon and sky) is my only physical, tangible connection to the women in Luminescent.

The chapbooks are each self-contained and can be read in any order, but there are strong connections and resonances across the sections. Why did you want to present Luminescent in separate chapbooks, rather than as a single collection?

At first I thought that whatever I published next after Girls of the Drift should be a full-length collection. I wrote Luminescent with the intention that it would be a normal book. But sometime during my MA year I discovered zines – handmade, DIY books that can be full of art, collage, photography, journaling, poems, anything – which expanded my idea of what a book can be. There are actually no rules. Maybe there doesn’t need to be a beginning poem and an end poem.

There are so many small presses creating beautiful chapbooks at the moment and so many excellent DIY poetry zines, so I thought: could this project be more like that? A bit weird and risky and unique? And now I’m so glad we took that risk.

Your debut chapbook also contained poems about real and fictional women – in the years since writing that, has your approach to writing about people or characters changed?

I started out writing poems only about other people, and now basically I can’t stop writing about myself. I guess for some it’s the other way around, but it took me a while feel like I could let myself in. Luminescent sits somewhere in-between. It started out much more historical and biographical, much more objective and factual (if poetry could ever be called objective), but then I realised I couldn’t keep myself out of the poems. I realised that the act of imagining is itself a signal of the writer’s presence. There was no point in me trying to be invisible anymore; and I think the work is better for it.

Biographical poetry is a really interesting area. Do you have some thoughts, both as a reader and a practitioner, of what poetry brings to writing about a life? Do you have any favourite biographical poems by other writers?

I love that poetry occupies an uneasy space somewhere between reality and imagination. That’s the work of poetry – weaving between the two, creating a portal from one into the other. I think that’s quite magical. There is so much room for questioning and unknowing, which is a valuable thing. Historical fiction can do similar things but I think in poetry there’s so much more breathing space. You can admit to openly knowing nothing but wondering everything, which is incredibly valuable when you’re facing a biographical subject who no one knows about, who has left behind little material trace of her life.

Two examples of auto/biographical poetry (and prose) that actually catalysed the writing of Luminescent are “The Glass Essay” by Anne Carson, which is about the speaker’s connection to Emily Brontë, and “My Emily Dickinson” by Mary Ruefle, which is actually an essay, where she draws a series of connections between Emily Brontë, Emily Dickinson and Anne Frank.

There are two wonderful poetry books that I think are key works of New Zealand biographical poetry – How to be Dead in a Year of Snakes by Chris Tse and This Paper Boat by Greg Kan. I discovered these poets during my MA year and I keep returning to their work again and again.

More recently I’ve fallen in love with the work of several mind-blowing American poets that all interact with biography and history and autobiography. Here’s a quick reading list: “Salome Dances the Seven Veils” by Nina Li Coomes, “Self-Portrait as Karintha” by Safia Elhillo, and Aubade with Burning City by Ocean Vuong.

Some of the poems in Luminescent are erasure poems. What I like particularly about your erasure poems is that, unlike many practitioners, you use a method of erasure that means the words underneath are still visible in a ghostly fashion, so while the poem emerges from the un-erased words, the context you have taken them from is still apparent. Why did you chose that method?

I find myself easily seduced by the mystery of erasure poetry. But there’s so much of it around – Instagram poetry, Tumblr poetry, all of that … which is not to say it isn’t any good. I love that it’s a visual kind of poetry, and that in order to create it you need more materials: something to erase with, something to cut with. It turns a poem back into something you’re making with your hands.

I decided to try making erasure poems after reading (if reading is the right word) Nox by Anne Carson, which is a monumental, heartbreaking work of poetry and translation and collage and visual excavation all folded inside a box. It’s like a box of evidence. One of her techniques is to paint over old photographs and scribble things on top of the whiteness, so you can’t really see what’s underneath, but you can see that something is there. I wanted to create a similar layering of past / present, document / poem.

What is it about whales?

Oh, because they are so enormous and beautiful but we know so little about them! We don’t really know why they strand. We don’t yet know where lots of species go to breed, or how different matrilineal lines communicate, or what they can feel––only that they do feel.

You wrote the first draft of this book during your MA year, as your folio. Did you go into the year knowing what you wanted to write?

I thought I did – I’m a very organised person who is good at making plans and lists. From the beginning it was always going to be a five-part collection of poems about women from New Zealand history. We soon realised that we had to be open to change. I may have stuck to the plan but the way I’ve gone about it is very different from how I thought it would be, which is a good thing. I read so much during the year (and not just poetry) that there were so many new things I wanted to try, so many new kinds of poems that I wanted to write.

How important to you are literary foremothers? Who are some of yours?

Our MA tutor Cliff Fell said to us very early on something along the lines of: being a writer means being a reader. I’ve heard it repeated many times since. So I try to read much more than I actually write. Long before I tried to write anything, my first foremothers were Katherine Mansfield, Virginia Woolf and Sylvia Plath. Then I discovered Anne Carson’s translations of Sappho – two vital foremothers – which made me want to try and write a poem. Non-white writers and poets (especially Asian writers) were largely missing from my university reading lists so there is always, always lots of catching up to do. I’m discovering new foremothers all the time: Maxine Hong Kingston, Claudia Rankine, Alice Oswald, Annie Dillard.

Literary foremothers get you started, but real life poetry sisters are just as important. They make sure you keep going.

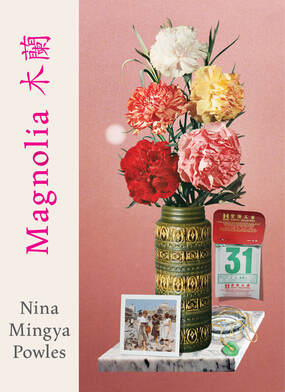

You’ve just spent a year and a half in Shanghai learning Chinese. Has being in a different country and immersed in a different language influenced your poetry? In what ways?

It has influenced me immensely in so many ways, but I found it impossible to write poetry for a long time. I discovered recently that Robin Hyde felt the same when she went to China, which makes me feel better: “in travelling, peace isn’t deep enough—if at all—for the writing of real poetry.” I kept a journal and scribbled fragments in it every day and I started writing mini essays about food, which I’m still working on now.

Learning Chinese is interesting for me because I’ve always been surrounded by it in small ways but never learned it properly I started at university, which means that so much feels familiar but so much is frustratingly out of reach.

Learning Chinese characters by writing them over and over again twenty times each night (it’s the only way to learn them) is slow work. It requires patience and discipline and makes you look at words and letters in a new way. In English, letters represent sounds but in Mandarin, only one portion of the character indicates sound; the other parts visually represent root and meaning. I often felt overwhelmed by so many characters and all their complex components, but also drawn in by their mystery and their beauty. I started experimenting with using Chinese characters in my poems that are otherwise written in English. I’m really excited by poets who do this, like Ae Hee Lee and Ya-Wen Ho and Jen Hyde. I like the idea of a poem containing many languages at once, not just Chinese / English but visual / textual, symbolic / phonetic.

The very first Chinese characters were carved into pieces of ox and turtle bone thousands of years ago. They were oracle bones; people would write out their questions on the bone, then the high priestess would hold a flame against it until the bone splintered and began to shatter, then she interpreted the pattern of cracks. I think I’d like to write poems like these – made of words and pictures and tiny cracks in between.

Find out more about Luminescent...