Below are the speeches by launcher Sean Molloy, and by John-Paul himself.

Sean's launch speech

My name is Sean, I’m an old friend of John-Paul’s and I just happen to be the husband of Helen, the publisher. But it’s in my capacity as an old friend with an appreciation of John-Paul’s work that I’m speaking to you this afternoon.

People have been asking me what Kaitiaki o te Pō is about and it’s a very fair question. You should be able to sum up what a book is about, surely? However the question always leaves me flailing, struggling for a simple answer.

On one level the book is a collection of personal essays with a wider eye than the personal, dealing with topics like a school field trip around India; John-Paul’s experiences of being a high-school Dean trying help the ‘difficult’ kids; and his realisation that the heroes of his university days, young men, such as Keats and the lead singers of grunge bands, are perhaps not the best people advise you how to get the most out of life after all.

The essays tend to take at least two apparently different topics and twist them together in artful ways that are surprising and insightful, leaving you wondering: how did he do that? How did he see that?

One essay features John-Paul getting a perm, somehow interweaved with his quasi-friendship with an unpopular boy in class. Out of these two apparently disparate themes, John-Paul weaves multiple reflections on the hidden hierarchies and structures that teenage boys, and by extension all of us, need to accommodate ourselves to and how those hierarchies can turn in unexpected ways.

You may be able to see the problem of summing these essays up by now, I hope. They’re not simple, they are special. There’s a phrase John-Paul uses in the book – “It was like trying to describe feathers with the language of lead”. That is a good articulation of the futility of trying to describe this extraordinary book.

But, because I am the launcher of the book, I’m going to do my very best to articulate what I think the book is about. Ready? Here goes.

To me, Kaitiaki o te Pō is a book about vulnerability. It’s a book that draws its power from embracing vulnerability.

First, John-Paul the narrator is vulnerable in his life, to time, to memory, to history. There is a consciousness and a theme that loved ones get older, change and are lost to us in multiple ways and that a fearful pain exists in that vulnerability. The first essay in the book expresses all this and is my personal favourite in the collection. It gracefully weaves together reflections on youthful nostalgia, the death of a good friend and Māori views of the world to find a place in the world for historians. Historians, John-Paul suggests, following the thoughts of Justice Joe Williams, are kaitiaki o te pō, caretakers of the night. The theme is one of power and purpose in vulnerability, that we take our dead with us and do our best to love and care for them through our memory.

As well as his own vulnerability, John Paul shows us the vulnerability of others, as people and as part of human systems. These are essays that are focused on people – people are the heart of them and caring for people is the point of them. This is a book that is acutely aware of privilege and the vulnerability that is the flipside from lack of privilege. The privilege and vulnerability of class and ethnicity, gender, income and political power. The systems that people create are more often the problem than a solution. Capitalism is an unescapable trap. The products that people create are after-thoughts and more likely to be rubbish than anything else – an empty chippy packet blowing in the wind, bottle tops washing up on the South Coast. Institutions are usually well-meaning but ineffective. The focus is relentlessly on the people stuck in these systems, and the love John-Paul has for those he writes about.

Third, John-Paul opens himself up to be vulnerable to us the reader, to our judgement. Certainly he doesn’t spare himself from his own judgement. This is not a book written by someone needing to be viewed in a rosy light, who wants to explore the problems of the world without looking at his own place in those problems. These are essays written by someone who has started with examining himself and then looking outwards – true personal essays, but not ending at the personal.

I’m at risk of making the essays sound like a downer. Well, here’s another thing, these essays are funny. Laugh-out-loud funny in places. The humour, though, is another dimension of the exposing nature of the essays that I’ve been talking about. The humour is yet one more way of being honest.

Finally, there is the vulnerability created by these masterful essays in us, the reader. We may not always be comfortable reading these essays. They can be confronting. But they’re so good. They’re remarkably well-written essays written from a high yet intimate viewpoint that refuses to let anyone off the hook but has love for all. There are no villains in these stories, there are people, messy people, trying their best. Vulnerable messy people. People just like us, in other words.

As John-Paul puts it: “An elaborate mess of cogs and springs, prettier than you thought, simpler and more complicated than you thought, Like most people. Like everyone.”

Read the book. Enjoy the book. Savour the book.

And then let me know what you think it’s about. Thank you.

John-Paul's launch speech

One of my aunts died last night. Aunty Audrey. She was 71.

Each year when I was growing up I went south from Wellington to see my relatives. Sometimes I flew down to Dunedin to stay with my Gran in Mosgiel, and sometimes my mother and I took the car across on the ferry and we drove south. When we drove south there was a routine. Christchurch meant stopping to see Aunty Helen and Aunty Susan and my cousins. Timaru meant Aunty Linda and Uncle Jack. Waikouaiti meant Great Aunty Helen. Alexandra meant Aunty Audrey and Uncle Neville.

I remember their house in Alex. It was actually nearer Clyde, up Springvale Road, a two storey house, and land, in a valley that baked hard and yellow in the summer, and froze hard and grey in the winter. I can remember going to collect the eggs from the coop one morning, and suddenly developing an aversion to soft-boiled eggs when they were presented at the breakfast table 30 minutes later. Being put on a horse and not liking it very much. Going looking for tadpoles with my cousins in the concrete shutes and sluices that ran down from a reservoir. Other things too. Like the terribly unfair way my uncle treated the sons compared to the daughters, and the seeds of resentment that were bedding in for later. Each time we went to their place the Clyde Dam was progressing. Each time we drove through we wondered if it would be the last time we took the winding, narrow road up the Cromwell Gorge. I remember the Cromwell Gorge as a set of little orchards caught between the road and the steep, rocky ranges; run down old wooden sheds, and tall grass; and on the other side, complicated, jagged rocks, stepping down to the bolting, blue water at the gorge floor.

When they moved to a house outside Mosgiel quite a lot about the complicated internal family relationships had begun to unravel, but I discovered jam and cheese sandwiches in their kitchen, and managed to defeat my much younger but highly rated cousin at a game of chess much to my mother’s silent pleasure.

My Aunty Audrey was easy going. I remember her as having tired, but friendly eyes, and an appreciation for self-deprecation. But enormously troubling things happened to her a lot, and the eyes must have been tired for a reason. The last time I saw her was also the last time I saw my Gran. Seeing my Gran again had rubbed me raw, and Audrey was talking about one of the children she had raised and how he was going to come home from Australia soon. It seemed obvious that he wouldn’t come back from Australia. He had a job, and a life, and got back some of the self-confidence he had been robbed of growing up. As far as I know he never did come back, although I suppose he is planning a trip now. For the funeral. I dismissed her talk of a homecoming as naive, but it was probably hope. Probably based in some regrets. But I don’t know because I never truly engaged with her life when I grew up. Never sat down and figured it out. Which is lazy and unfair.

I try to get it righter in retrospect. That’s some of what I am doing when I write I think. Trying to look back to understand now: understand the students in front of me, the injustices in the world, the causes of the feelings I have about myself and others. One of the things I am worst at is saying how important people are to me in the present. I’ve begun to understand why that is, but it’s still hard. But this is a time when it is right to do it.

I want to acknowledge a few people. And I want to invite three people to the room.

When I wrote this originally I wrote: “thank” – I want to thank some people. But it’s not a “thank you” I want to give. It’s to say: “I see you, I see what you have done, I see how you have shaped me, made me better, taught me things, and I acknowledge that and I hope I have been something good for you, at times, in turn.”

So I want to acknowledge my family. My mother, Cathy, Eleanor and Rosamund. Remember what I said acknowledge means: I see you, what you have done, how you have shaped me, made me better, taught me things.

I want to acknowledge my friends. My childhood friends, like James, my school friends, like Steve, my uni friends like Danyl, Richard, Adam and others. Their partners. Their children. It turns out we have gotten older together. I’ve not been the best friend to you, really. I’m quite grumpy and sullen. Take this an apology and an acknowledgement then.

I want to acknowledge the people I work with and have worked with. The teachers and the students. You need to be thanked for all the laughter, and all the shared effort to be better. I see teachers and students as being in a complicated collaboration: teaching and learning from each other. I have learnt a tremendous amount from you.

Especially, in relation to this book, I want to acknowledge Sean and Helen. This book happened because of them. Because they saw I was sad and they took me out and we talked and they put a new path in front of me. A path towards a book. owe them both a tremendous amount. Especially considering my long history of being a poor correspondent, unreliable dinner guest and ingrate. Thank you.

And now I must invite three people to the room who cannot be here.

The first is Matt.

When my friend – who was a friend to many in this room also – died in 2012, I was devastated. The solitary positive thing that came out of his death was my renewed understanding of the importance of connection. That sharing loss gives us a little power against death. We don’t have to be entirely naked in the face of our mortality. So I invite you here Matt because you always believed in me. You always said I would write a book. You accepted as inevitable that I had talent and that others would appreciate it. And I always thought, but never said: “Why?” I never said it because you were so confident. Because your belief was complete. And so, I need you here so that I can thank you.

The second is Gran.

I stayed with my Gran in the school holidays a lot in the 1980s and those times are a rock, and an anchor to me in a time that otherwise often felt confusing and lonely. Each day of each visit to my Gran’s had the same rhythm. The same rituals, the same quiet presence of love behind the most prosaic quotidian tasks. I apologise for getting older and thinking too much of myself. For not coming to see you more often in my twenties. I want you to know how much our time sits with me even now. When you died it was time. I was there to take the handle of your casket. But I’m older now and I still want to say, so that you hear, “I love you.”

The last is my father.

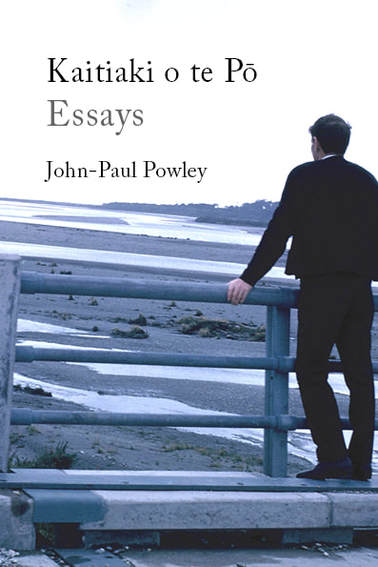

He’s on the cover of the book. Looking away. There, but not knowable. He died when I was five and I remember almost nothing of him, and nothing clear and concrete. When I became a father at 33 I went looking for him. Down south. With the people who had known him. The few who were left. It was illuminating and frustrating. As if I could sharpen the focus on the photo of him on the bridge, but not get him to turn around, and look at me. What my trip down south and my interviews did was change my relationship with him. I stopped ignoring him, downplaying and erasing him, and I let him come back. I accepted the pain of it. The confusion of it. So that I could also hear about his love, and gentleness and compassion. His death was one of the detonating events in my life, and it has only been in the last few years that I have realised that the fact of that makes me who I am.

So I ask him here today to say sorry. Sorry I forgot you. I won’t do that anymore.

***

I like to think that the orchards and the old huts are still there in the Cromwell Gorge. Submerged under the wide, flat reservoir waters that rose above them; that built behind the completed concrete buttresses of the Clyde Dam. I like to think that we can go back. That we can slip off the surface and plunge into the depths and see the past, and learn from it. That the past can be medicine. That it can make me better. More compassionate. More loving.

My Aunty Audrey had dementia. Her memory was unmoored. She is gone now, but I still have a duty to her. To understand her better. To make the time to see my cousins.

I remember Matt, Gran and Dad. And I have a duty to my family, friends and colleagues.

Thank you for being here. It means a lot to me. I’m very lucky to know you and I rarely say it. We’re important to each other, and I look forward to being able to celebrate your achievements with you in the future.

Thank you.