Thanks so much to everyone who has supported this book by coming to the three launches we've had - one in Amberley, one in Christchurch and the last in Wellington (the first ever event at Ekor Bookshop Cafe, which was a wild success) - and of course by buying the book!

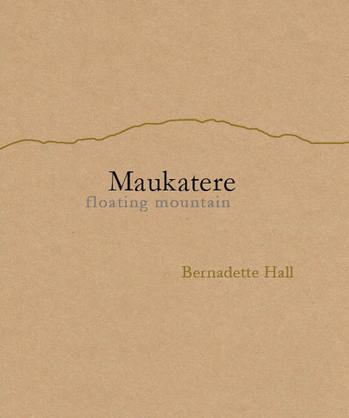

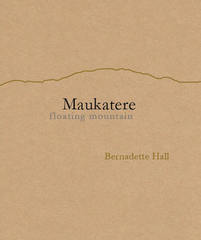

Author: Bernadette Hall

I’d say the genesis was three years ago. I’d already moved into writing about where I live, the rural, beachy scene at the northern part of Pegasus Bay. Poems which later appeared in Life & Customs (VUP 2013). John and I moved out here, bought a dilapidated bach made out of polite (that’s an asbestos based material. We’ll choke on the fumes if it goes on fire and I gather it will explode then as well). The shift north from Fendalton, Christchurch, was a move into freedom, in 2003. A move, in a way, into the 1920s and into simplicity. Into a Kiwi dram/cliché. Only about 90 people live here at the beach, which is stony with colonising waves that nibble at the stony margins. Safe swimming is possible only at low tide and only for two months of summer. In its own way, the move was one of resistance, I’d say. It can be very quiet out here and the huge sky and the stars are wondrous.

It is in a different, more experimental form than most of your work. Where did this come from? Is it a direction you will continue to follow?

I began playing with bits ‘n’ piece: an old diary from 1985; a couple of old letters; family stories; phrases I’d gleaned when living in Ireland in 2007. Also I’d joined a wonderful trekking group, The Mountain Goats, average age about 70 but all fantastically fit, men and women, most with a farming background. We go out every Monday. So I’ve walked the landscape, downs, ‘mountains’, paddocks, rivers. I’ve worked myself into it. And then there’s the different tugs of history. Not so many people use the name ‘Maukatere’ (the Māori name for Mt Grey) out here. It’s so beautiful. I wanted to hold up the beauty of the name and trek around it.

Maukatere is in the Hurunui, near Amberley, the area in which you now live, and your book honours that place. But you are a comparatively recent resident there, and your own originating landscape is further south. Have you an itch to write a sequence about that?

I wrote about Dunedin in Life & Customs, in a longish discursive text that ends the book – it’s called ‘Tulliver’s Maze’. That was like opening a door – something that I’d like to open up further. It wasn’t a struggle for me to write Maukatere; it felt and still feels inevitable to me. Something about trusting the stuff that makes me who I am.

The figure/character of the tangler recurs in the poem – can you talk about the tangler and what he means to you?

I’m a great admirer of [Waiheke artist] Denis O’Connor. He created the beautiful cover of The Lustre Jug (VUP 2009) for me. He was the first to hold the Rathcoola Fellowship in County Cork in 2005. I had that experience in 2007. So we inhabited the same landscape. I admire the works he continues to create that explore the theme of The Tangler [a trickster figure at traditional Irish horse fairs]. I think Rachel has caught that tangly theme in her drawings. All that layering that occurs in and between the arts – that mysterious and loaded tangling. The act of collaboration feels like a kind of divinely inspired tangling. Also, I can’t help but laugh at the tangles that beset my Tangler, the writer, me I guess, all of us. Insight and self-mockery all tangled up there. That last statement from him, about being a victim … ‘isn’t it always the way’ … I find it utterly hilarious. It’s one of my favourite bits in the whole text.

Artist: Rachel O'Neill

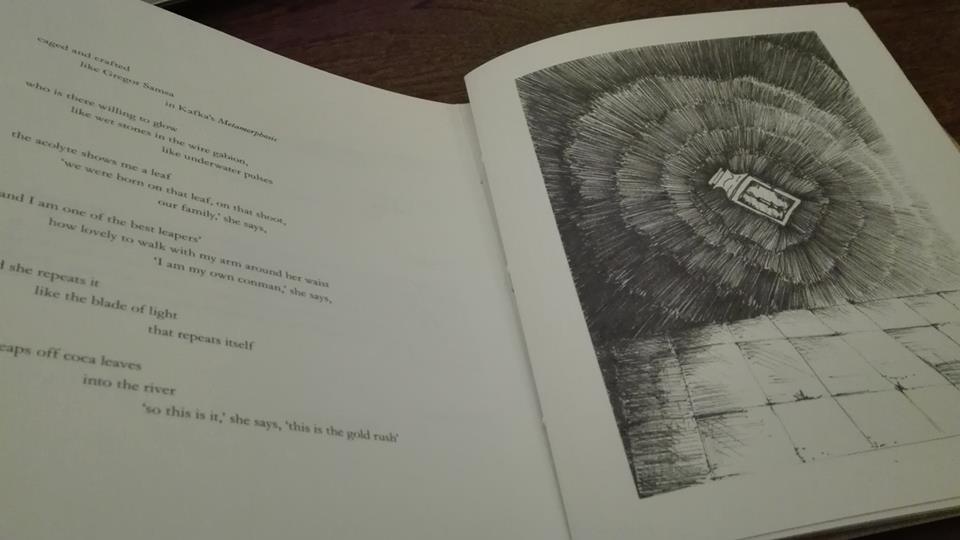

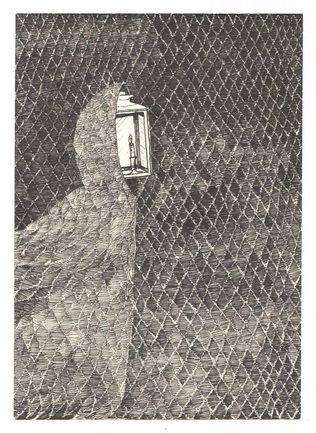

Jim Harrison, an American author, once said ‘Your best weapon is your vertigo’ and when I read an early draft of Maukatere: Floating Mountain that Bernadette sent me I fell through place, time, memory, love, separation, ancestors and new generations. It was a feeling of vertigo, and yet a state of mind used a bit more like a resolute mirror, to catch confronting and comforting reflections, angles and lights. And life can be turned upside down. So just when you think you’re going down, you’re leaping skyward, and there’s a view and a new sense of perspective. So the poem seared into me in a very personal way and the lines, Bernadette’s extraordinary lines, were an artist’s dream. So evocative, and full of emotion that could walk the talk of realism and surrealism with equal conviction. A character emerged, the Hooded Lantern, a figure who wears a hoodie and who has a lantern for a face. From there the Hooded Lantern journeyed around Maukatere, a mountain shaped for me through Bernadette's words, a place that I hadn't yet visited and yet was becoming connected to through our collaboration.

Well, I’m definitely more interested in what other people think of the Hooded Lantern, as I hope the character takes on many different identities. You could say that the Hooded Lantern is a figure sometimes getting it wrong and sometimes getting it right, not entitled to know and understand everything on this journey around the mountain exactly, and yet curious and keen to bump into the locals, keen to shine a light that doesn’t leave a mark, except perhaps in memory, which will need to be kept alive by someone, if considered of value. It depends on who remembers, who thinks it’s important enough to speak of again. Or who asks the right question and shows an interest. So there's an intergenerational responsibility. Bernadette’s poem is a fabric of memory and her words explore what it means to be known by other people and know them in return. We give ourselves over and we are given back to ourselves, shaped and reshaped. We emerge somewhere in the to and fro.

The Hooded Lantern was sparked by Bernadette's words. It is an adaptable character, too, and has appeared in a few of my projects now. In Bernadette’s book the character perhaps symbolically hints that place is really a face, a face is really a place – either way, we’re eye to eye with our responsibility. The Hooded Lantern is a bit different in my graphic essays, more of a hipster, self-conscious about having a lamp for a face, yet possessing a reasonably strong sense of what home means and how important it is when fumbling around out in the world. The Hooded Lantern generally comes to see, even if by accident, what is actually in front of its beam - so in a strange way it eases up on the habit of projection, if you don’t mind the pun, and takes in all the bewildering, miraculous, violent, delicious sights of life that we all must reconcile in relation to the home place/face.

- Find out more about Maukatere: Floating Mountain

- Read Rachel O’Neill’s graphic essays on her website